1st published in IHRM Magazine, Wellness and Selfcare edition, October 2021.

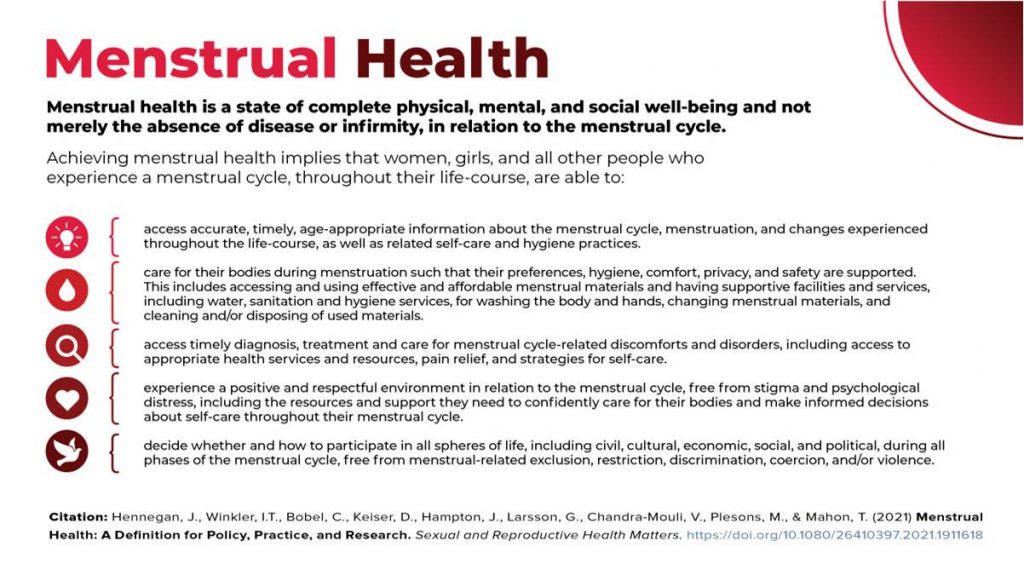

If you were reading the caption above before May 2021, you would be right in questioning the validity of this statement. However, post May of this year, a revised global definition of Menstrual Health was released by the Global Menstrual Collective Terminology Action Group comprising of a global team of 51 experts from Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americans. This new definition (Hennegan et al, 2021) which is grounded in the World Health Organization definition of Health states that menstrual health is

“A state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, in relation to the menstrual cycle”

This definition was developed to advocate for the inclusion of menstrual needs in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). According to Loughnan et al, 2020, the ability of menstruators to manage monthly menstruation requires three distinct components which are: one, assets such as sanitary products, water and soap; secondly services such as information and education; and thirdly, spaces such as safe and convenient sanitation facilities. These three collective components have been termed Menstrual Hygiene management (MHM) by experts in the WASH Sector. It is expected that places such as workplaces for instance should be supportive of MHM by ensuring that they cater for these three components. Unfortunately many workplaces do not do so and if so, not adequately and this negatively affects menstruators. Furthermore, the ongoing stigma around menstruation hinders the action of adequately addressing these three components in many contexts globally.

The question then is, how can HR play a role in ensuring that MHM is adequately supported at the workplaces?Well in my view, there is a checklist that HR can reference on achieving menstrual health managementat the workplace that has been tabled by the experts. This checklist can be applied by HR towards ensuring that during the course of the working life of menstruators,HR should do the following at the workplace:

Provide Information about the menstrual cycle;

Menstruators should be able to have access to accurate, timely information about the menstrual cycle, menstruation, and changes experienced, as well as related self-care and hygiene practices.In terms of self-care, keeping pain medication in the first aid kit can be helpful. Also,incorporation of MHMtrainings as part of wellness training from service providers as well as ensuring relevant pamphlets and such like information is available within the office.

Cater for Materials, facilities and services;

Enhance self-care for menstruatorsby ensuring that their preferences, hygiene, comfort, privacy, and safety are supported. This includes accessand use of effective and affordable menstrual materials in the washrooms for emergency use. Also, having supportive facilities such as water, sanitation and hygiene services, for washing the body and hands, changing menstrual materials, and cleaning and/or disposing of used materials.Another recommendation is to have a suggestion box that allows for critique and suggestions about materials, facilities and services by menstruators in a private and dignified manner.

Create an enabling environment for diagnosis, care and treatment for discomforts and disorders;

This can easily be done through incorporation of wellness programs that will allow for access to timely diagnosis, treatment and care for menstrual cycle-related discomforts and disorders, including access to appropriate health services and resources, pain relief, and strategies for self-care. Examples of these wellness programs could be for mental health support and gynaecological support. Identifying service providers that menstruators can easily access at the cost of the employer would be beneficial. This service should also benefit men working in the organization with wives or partners who are experiencing discomforts and disorders.

Promote a positive and respectful working environment;

Promote an organizational culture that allows for menstruators to experience a positive and respectful environment in relation to the menstrual cycle, which is free from stigma and psychological distress, including resources and support they need to confidently make informed decisions about self-care throughout their menstrual cycle.

One way of doing this is to sensitize men on the issue of menstrual health. Lack of understanding and appreciation of vulnerabilities during menstruation leads to misinformation, stigma fear and exclusion. Sensitization creates empathy for what women are going through, be able to offer support and most importantly, be involved as ambassadors/change makers/champions. In this role, they challenge the status quo of myths, misconceptions, taboos cultural beliefs and practices that promote discrimination through shame, fear, and lack of dignity for women during menstruation. Additionally, it is also an opportunity for men to interact with menstrual materials as a step into normalizing menstrual conversations even in their own homes and communities.

Advocate for freedom to participate in all spheres of work-life.

Champion participation in all spheres of work- life during all phases of the menstrual cycle, free from menstrual-related exclusion, restriction, discrimination, coercion, and/or violence. HR should ensure that they have engendered policies to address these concerns.

In conclusion, according to the global menstrual collective website, the importance of menstrual health and hygiene to various human rights was enshrined in September 2018, when the UN human rights council adopted a resolution on human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation that specifically included menstruation. The resolution expressed great concern over lack of adequate water and sanitation services including MHM in workplaceswhich was seen to negatively affect gender equality and safe and healthy working conditions among other human rights infringements.

As HR practitioners, I believe it is high time we played our part in remedying this wrong.

References

Julie Hennegan, Inga T. Winkler, Chris Bobel, Danielle Keiser, Janie Hampton, Gerda Larsson, Venkatraman Chandra-Mouli, Marina Plesons & Thérèse Mahon (2021) Menstrual health: a definition for policy, practice, and research, Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters, 29:1, DOI: 10.1080/26410397.2021.1911618

Loughnan L., Mahon T., Goddard S., Bain R., Sommer M. (2020) Monitoring Menstrual Health in the Sustainable Development Goals. In: Bobel C., Winkler I.T., Fahs B., Hasson K.A., Kissling E.A., Roberts TA. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7_44